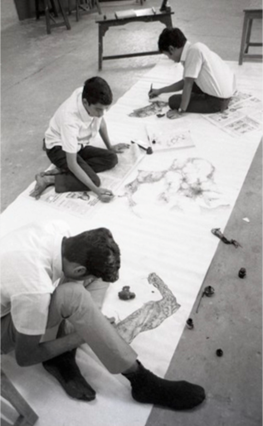

Artists on campus at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda, c. 1970. Images courtesy of Asia Art Archive and Jyoti Bhatt.

My doctoral dissertation studies the development of artistic practices at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Baroda, founded in 1950 as the first art school established in an independent India. From the 1960s to 1980s, the Faculty incubated three generations of Indian modernists, many of whom arrived as students and continued to teach in the same departments. While individual artists from Baroda have been studied, the presence of a close-knit artists’ community in Baroda has remained largely unexamined in art historical scholarship thus far. Further, scholars have primarily analyzed their artworks in formalist terms as “narrative-figuration,” reflecting a tendency in Art History to categorize artists by singular stylistic affinities.

During my conversations with artists from Baroda, I expected them to discuss the development of these artistic styles or their pedagogies in the classroom. Instead, our conversations turned to anecdotes about their teachers’ homes, jokes about students cooking, dancing, or travelling together, and memories of a “homely” atmosphere on campus. In response, my project recontextualizes their artworks by examining the influence of sociality and camaraderie, challenging the idea that a stylistic label can be easily applied to the narrative of the Baroda school. By studying works of art through a lens of community, my dissertation opens up a new way to consider art pedagogy—as one that unfolds both within and outside institutional spaces. I view Baroda as an entangled network of interpersonal relationships across generations of Indian modernists, who are in dialogue with both local communities and national agendas. I argue that this framework of entanglement has implications for the study of postcolonial modernism globally, since it allows us to consider artworks as outcomes of collective exchange rather than stylistic innovations or avant-gardism of individual artists.